Software, the Moving Target

Yukihiro “Matz” Matsumoto, creator of the Ruby programming language, gave a fascinating keynote talk at this year’s RubyWorld conference the other day that left me thinking. It was a talk about Ruby, about the recent history of software, but also about much more than that.

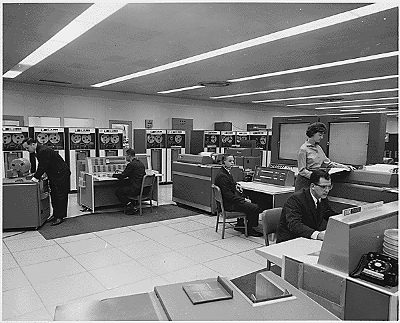

In his trademark style, Matz recounted this history through the story of his own life. That story begins just before he first created Ruby, 20 years ago, in an era where hardware was expensive, software took years to create, and documentation was measured not in number of pages but in centimeters of thickness.

“20 years ago, we should have admitted our ignorance.”

Software was like nothing mankind had ever created before, a digital embodiment of human thought. But too much money was invested in hardware and infrastructure for companies to admit to clients that they knew nothing about how to build it. Failure was just too costly.

Now, looking back from an era where hardware is cheap, software is commonly developed in weeks or months, not years, and documentation is measured in commits, not pages, some things become clear.

The first is that our basic assumptions were wrong, foremost among them the assumption that “we know what we should make”. Were this true, software development would simply be a matter of specifying requirements, setting out a plan based on those requirements, and executing the plan.

Except, that doesn’t work. Or at least, it doesn’t work very well.

Before creating Ruby, Matz himself worked at a company producing enterprise software this way, with large projects executed over many years and code written to specification, waterfall-style. Clients said what they wanted, specifications were drawn up, and programmers wrote code to satisfy those specs.

And in end, something was produced. It may not have been very satisfactory, or even satisfactory at all, but there was something to show for the many years of time and resources invested, and that something was produced on schedule. That was the minimum requirement.

But twenty years ago, Matz already felt that something was wrong. The big projects at his company treated software just like automobiles, or cabinets, or toasters, something to be designed, manufactured and delivered. But code is not physical, it’s digital, and it follows a different set of laws.

The challenge of grappling with those laws was vastly underestimated then just as it is now. The word “software” itself, coinded to describe the stuff being coded, evoked the wrong image: software was not “soft” at all, but hard. Very hard.

“Software may be the most complex thing ever created by human beings.”

It is fascinating to me to think that software is at once one of the most complex things we have ever created, and also something that defies our basic instincts about what it is to “create”. Thousands of years of blood and sweat have been spent learning to build things in the physical world, so it’s not exactly surprising that we want to apply these lessons to the digital world.

But they fail us, Matz said, and not in a good way – at high cost, without teaching us anything. They fail us because we are not developing software in a predictable, cartesian world like the one we live in, but in an abstract world that is unfamiliar and constantly changing.

In this world, where our real-world instincts are often wrong, we need to try and fail often, in a repeatable way, and cheaply. Large projects of the kind Matz had been working on 20 years ago do exactly the opposite.

The message was not exactly new, but Matz expressed it with such simplicity that it seemed self-evident. He did not profess to have the solution to the problem, or even suggest that there was one solution to the problem, but only offered some hints drawn from experience.

“Keep moving,” he said, advising against the conservative “ostrich” strategy of putting your head in the sand in the hope that things will return to normal. (They won’t.)

“Work hard to code less,” he said. Collaborate, leverage others' work, use existing tools. In other words, stand on the shoulder of giants. This made a lot of sense to me.

“Write great code. Change the world.”

Ultimately though, this was the most powerful message. Ruby was designed to make this possible, by maximizing programmer happiness. But Matz, to his credit, hardly mentioned Ruby. He was thinking more broadly.

And when thinking more broadly, something struck me as curious about the whole gathering at RubyWorld.

Here we were, brought together by a programming language named Ruby. Ruby was designed by one programmer in his free time at a large corporation producing enterprise software to specification. Twenty years later, this programming language is used around the world, forms the foundation for one of the world’s most popular web frameworks, and has arguably elevated Japan’s status and visibility in the global technology sphere.

The fact that this programmer had the free time to develop Ruby was pure luck. Certainly nobody at his company ever allocated time to develop a quirky programming language to build better software by increasing programmer happiness.

The situation today is not so different: industry and government invest massive sums of money in large, expensive projects destined to the dustbin of history, while largely ignoring a homegrown success story right at their doorstep.

Now here was the creator of Ruby telling us that the existing approach to building software is wrong. Were Matz not such a gifted storyteller, this message might come off as arrogant or paternalistic. But it didn’t.

And yet.

I watch everybody nodding their heads in agreement. But are they really listening?

For a core group of hackers and entrepreneurs mostly in Tokyo, early adopters of every new technology, what he’s saying is old news. They’ve heard the message before – by now, many have internalized it. They’re looking into their laptops as he speaks, acting on his advice without even hearing it.

Matz isn’t really speaking to them. He’s speaking to everyone else. And he’s trying, in his very personable, self-effacing style, to get a message across to them.

“If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that! ”

Software is not just something which affects software developers. Not anymore. It’s not just in the computers, it’s in the automobiles and the toasters, too. It won’t be long before it’s in almost everything.

And just as it is hard for software developers to build software, so it is hard for everyone else to understand software, and the potential of software. People look to lessons from the past. When those lessons do not provide useful clues, they stick their head in the sand, hoping things eventually return to normal.

But they won’t.

Software is fundamentally different. It’s a moving target. Simply to keep up takes enormous effort – to actually push the boundaries, you need to run twice as fast, think twice as hard, stretch your imagination twice as far – so most people just stick to doing the same thing, and demanding more of the same thing.

We need to change more than just how we create software. We need to change how people understand software.

And in that sense, watching his talk, it seemed to me that Matz the storyteller was at least as influential in today’s world as Matz the programmer was 20 years ago. Ruby is a language that changed how programmers write code. The lesson of Ruby is a story that could change how people understand code.

That’s a story that I want to read.

Posted on November 27th, 2013.